Structured products are like mythical creatures. You might be wondering, ‘How do structured products work?’ Many investors have never seen or even heard of them.

Yet many folks do have a significant lump sum invested in a structured product.

Structured products have some eye-grabbing headlines. Some offer returns exceeding 10% per year. Others offer stock-market style returns with capital protection.

However, they’re also complex, misleading and often misunderstood. I hope this article will help to put that right.

I will lift the veil on these mind-boggling investments, to help you decide whether they might be appropriate for you.

The best structured products books will provide an incredible amount of depth and detail compares to this article, so please check those out, or perhaps books about derivatives, if its the financial instruments element which interests you most.

What is a ‘Structured Product’?

Structured products are a form of ‘IOU’.

It might look and sound like a stock market investment, but you are actually entering into an agreement with a single financial institution. This counterparty is usually an investment bank.

Structured products cannot be held within a stocks and shares ISA.

Structured products advertise attractive headline rates of return. However, the actual amount that you will receive back is actually variable. The agreement you sign will clearly set out the rules which govern the payment.

These rules link the payout to the performance of external indexes, such as the FTSE 100. You may receive back less than the advertised return, and in some scenarios, you may suffer a loss.

Example of a Structured Product

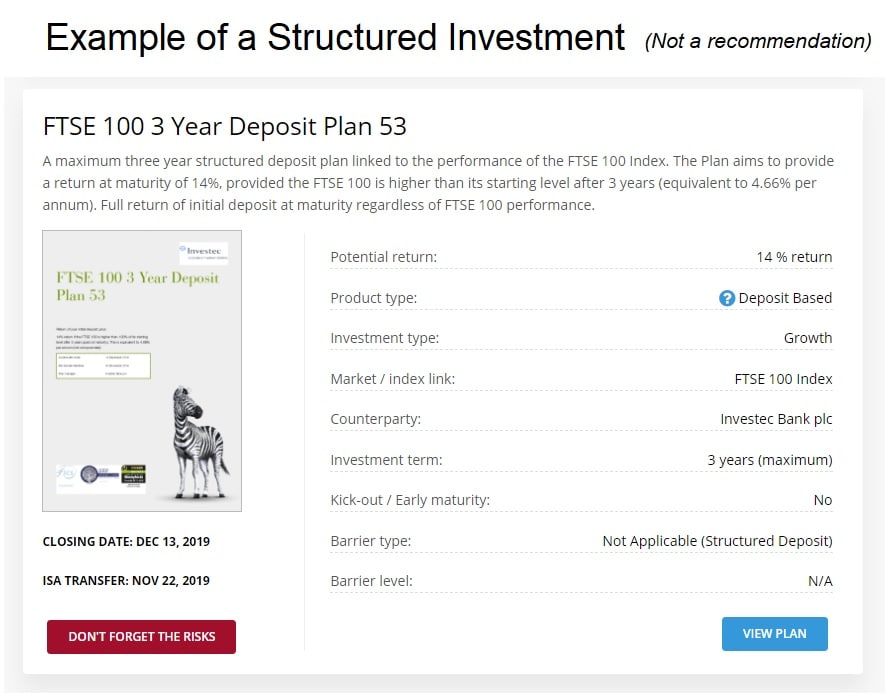

The following is an excellent example of what a lower risk structured product looks like:

The investment above offers returns of 4.66% per year for three years.

The catch is that it only pays this return if the FTSE 100 index closes the three year period at a higher level than it began.

If the index closes below its starting level, then the provider will only return your original invested amount at the end of the three years.

This is quite a strange investment!

- FTSE 100 doubles, you will earn 4.66% per year.

- But if it rises by 1%, you will earn the same 4.66% return.

- If the FTSE 100 falls by 1%, you will receive your original deposit.

- However, if the FTSE 100 falls by half, the provider will still return your stake.

This is a very different set of outcomes to an ordinary stock market investment in the FTSE 100 – where your return is based on the actual return of the index.

Overall – you are giving up the chance to participate in a large stock market rally but, in exchange, you are protecting yourself against downward movements.

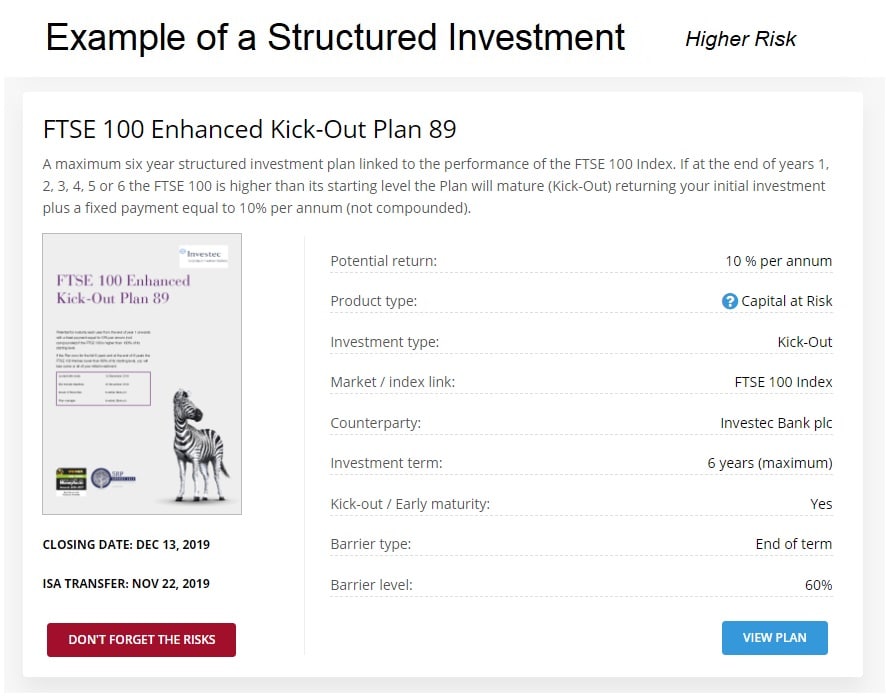

Let’s look at a structured product which offers higher returns:

This investment appears to be very generous. It offers a whopping 10% per year, potentially for six years. That’s a potential total return of 60%.

This is actually a higher return than you could expect from the stock market overall. (It has historically returned 5 – 8% per year over long periods.)

So, what’s the catch here then? There are two new catches: Kick-out and loss of capital.

Kick-out

Firstly, the rules state that if the FTSE 100 is above its starting level on any anniversary of the starting date – then the investment will ‘kick out’. This means it will return money to investors early together with the return to date.

So this might be a six-year investment, but it might not. In fact, there’s a very real chance that you will receive your money back after just twelve months.

That’s not so bad, though. I would accept a 10% return!

Capital loss

Although it isn’t clear from the summary, the terms and conditions state that if the FTSE 100 has lost more than 40% of its original value by the maturity date, you will suffer the same % loss as the FTSE 100.

This means that if the FTSE 100 has fallen by half, you will only receive half of your investment back.

The summary image calls this the ‘60% barrier’. I.e. until the FTSE 100 drops beyond 60% of its starting value, you will not suffer a loss.

To learn more about the different levels of structured product protection, see our dedicated article.

How do structured products work?

When I first discovered structured products many years ago, I scratched my head. I looked at the strange pattern of returns and wondered, ‘how do structured products work? What are they investing in which ensures they can meet their promises?’.

A structured product is a black box. Magical returns appear from it, but providers do not publish the inner workings to educate investors as to how structured products actually work.

You should never invest in a product that you do not understand. Without a clear idea of the mechanics of an investment, you will not ever feel fully informed of the risks.

So, here’s how structured products actually work:

How structured products work: it begins with a bond

Let’s begin with an investment that includes full capital protection. Let’s use the T&Cs of the first investment example above:

- 4.66% return per year for three years (14% total) if FTSE 100 closes higher

- Original investment always returned

If an investor deposits £10,000, the investment manager must pay out at least £10,000 in all scenarios.

Therefore it finds a low-risk bond yielding 3% per year and invests £9,157. This is the amount which, if left in the bond, will grow to £10,000 by maturity date.

This bond takes care of returning the original stake. The provider now has £843 to use to generate the potential 4.66% return.

Could the investment manager also invest this in a bond (growing it to £919) and hand this to the investor on the maturity date if the FTSE rose?

This wouldn’t work. In the favourable scenario, the investor would see only £10,919. That’s less the advertised return of 14%.

It also leaves the investment manager with a spare £919 if the higher FTSE condition isn’t met.

How structured products work: the manager turns to derivatives

What happens next is financial wizardry. The investment manager needs an extra bonus return if the FTSE 100 rises, and has £843 which it can afford to lose if the FTSE 100 falls.

The manager strikes a deal with a party that wants the opposite. It works like a wager on the direction of the stock market. The manager agrees to pay £843 if the FTSE falls, in return for a £557 windfall if the FTSE rises.

A bond and a bet. This is the portfolio that sits silently behind the prospectus. A bond will return the £10,000 capital, and the third party will pay £557 (plus the stake of £843) = £1,400 in the event that the FTSE 100 rises.

If the FTSE falls, the manager will pay the £843 insurance to the third party, but will still have the bond proceeds to repay the capital to the investor.

Making wagers with other institutions is a key part of creating such an unusual product. These deals are called financial derivatives.

How can a structured product return 10%+?

Given that most of the investment is placed in a low-risk bond, you might now be wondering how a manager can possibly generate advertised returns of 10%.

Let’s take a closer look at the second investment I showed above. Here’s a reminder of the T&Cs:

- 10% return per year if the FTSE 100 ends year 6 higher than starting level.

- If the index is higher than its starting level on any anniversary, the investment pays out early and closes.

- If the investment reaches maturity and the FTSE 100 has fallen further than 60%, the investor will suffer a loss equal to the FTSE 100.

- Otherwise, the original investment is returned intact if the FTSE 100 closes lower.

So – how does an investment manager achieve this feat?

They still invest a portion of the investment in a bond. Again, they will spend the leftover cash on derivatives which will provide a bonus if the FTSE 100 rises.

But this is all very similar to the first example – where does the extra return come from?

More risk means a higher return

The answer is that the managers can afford to buy larger derivatives, i.e. they can place larger wagers on the FTSE 100. Where does the extra cash come from? Well, it’s all because of that capital protection clause.

As an investor, it sounds normal to be told that if the stock market falls – you will lose money. But when you consider that structured products are backed by a low-risk bond – the capital loss risk begins to look very artificial. And that’s because it is.

The investment managers actually CREATE the capital loss risk, and use it to fund your higher return.

Those capital losses aren’t caused by real investment losses on the underlying bond – they’re the result of another derivative entered into by the investment manager:

“If the FTSE 100 falls by 40% – 100%, we are prepared to compensate you with £4,000 – £10,000 respectively. What’s that worth to you?”

This deal would provide someone with a large and very welcome payout if the stock market were to crash. The manager will receive a considerable sum of cash in return for taking on this obligation.

It’s this cash which enables them to boost the size of their FTSE 100 wagers to create a much higher bonus return.

In a straight forward way, the manager has created a trade-off. The investment will perform terribly in poor market conditions, but will provide a sweet return in the good times.

Why structured products aren’t as great as they might seem

Now that we know what is going on behind the scenes, we can actually pull out some interesting points that all investors should know before they invest.

Reason 1: The relationship between risk and return still holds

A key concept to grasp at this stage is that the manager hasn’t done anything extraordinary or used a high degree of skill in selecting these investments.

Each investment or derivative they have entered into has been at market prices and should simply deliver a fair return for the risks taken.

They have simply taken very specific risks in order to maximise the return they can promise an investor.

Therefore, if you ever find yourself viewing a structured product offer as being a ‘superior’ opportunity to the stock market, take a risk reality check:

You will always have a similar expected return per unit of risk. A structured product usually involves less or more risk than a typical equity investment. Structured products are not get-rich-quick schemes – they don’t break a formula or invert the laws of investment physics.

Reason 2: Our psychology gets in the way

Structured products appeal to investors because they take advantage of two elements of human psychology:

- Our aversion to losses, however small

- Our fixation on initial investment costs rather than opportunity costs

These get our brain quite excited about structured products. To the point where we might accept one which is mathematically worse than other investment opportunities you have rejected. Here’s how:

Loss aversion

Virtually all structured products carry an element of capital protection.

They’re designed to appeal to investors who are averse to losses. Specifically; those who don’t have a high enough risk appetite for the stock market, but still want to beat a bank account.

The complex pattern of returns offered by structured product look like a cynical attempt to hoodwink loss-adverse individuals into exposing themselves to huge losses.

In our explosive reason #5 below, we show how structured product investors could incur triple the losses of an ordinary shareholder if an index falls by 40%. Although there is only a small chance of this occurring in any given year – such an event will occur again.

Investors are being sold a risk profile that ‘feels’ safer to them due to the risk trade-offs. This could be in spite of the investment mathematically containing the same risk as any other similarly yielding investment.

As humans, we are so averse to even small losses, that we want to eliminate them, even if it means producing an extremely negative outcome in the worst-case scenario.

In my opinion, cautious investors should be sold cautious investments – not ones which offer no protection in the event of a serious market crash.

Opportunity costs

We also fail to acknowledge the opportunity costs.

When a brochure promises the return of our original investment if the FTSE 100 falls by 5%, this feels like a good outcome. Because we get back every penny, we don’t chalk this up as a loss.

But if we had put the money in a bank or peer to peer lending account instead, we’d have more money. Therefore a nil return after a number of years is a loss.

Our failure to notice opportunity costs means that investors may interpret many outcome scenarios more positively than they should. To only receive back your starting investment after 6 years is a disaster.

Reason 3: Opacity means hidden fees

As we said above, a structured product is a black box. Investors are not granted the privilege of seeing the underlying portfolio of bonds and derivatives.

This is entirely legitimate because the relationship between an investor and a provider is an IOU – a promise to pay. Investors have no claim on the portfolio itself, only on the company as a whole.

The portfolio is just the mechanism the provider uses to be able to fulfil their promises without taking on any risk.

While it’s legal to pull the wool over an investor’s eyes, the secrecy means that investors cannot gauge how much profit is being made in the dark.

Providers lock in a profit by holding back some of the cash that could be used to purchase the derivatives which offer the bonus return. Without this profit-taking, the portfolio could have been able to offer a higher rate of return.

Little is published about the profitability of such products, but the fact that their sponsors are often investment banks leads me to conclude that the margins must be high. The fees must be higher enough to convince these highly paid bankers that it is worth their while.

Read more: The best investment banking books

A key driver of investing success is to reduce or eliminate investing costs. This can only be achieved by cutting out middleman or choosing the most efficient investing option. Structured products achieve neither.

Reason 4: Indices are not the whole stock market

One of the secrets of structured products lies in the confusion between ‘increases in the FTSE 100 index’ and ‘stock market returns.

The two are not the same thing. But investors can make the understandable mistake of confusing the two.

As we explain in our guide to shares, investors experience two types of returns; increases in prices and dividend income. The FTSE 100 index only measures share prices, it therefore will therefore lag behind the total returns of investors.

Why does this matter? It matters because investors are likely to think back to statistics about shareholder returns, rather than index increases, when assessing the probability of a FTSE 100 rise.

For example, in our article about investment time horizons and building a portfolio, we quote average stock market returns as being 5 – 8% per year.

Therefore, this confusion can lead investors to overestimate the likelihood that a structured product will hit its index target.

Reason 5: Goodbye, dividend cushion

As an investor in a structured product, you do not receive dividends because your money never touches the stock market.

This fact comes into sharp focus when we look at how capital losses work.

As a reminder, in our example investment, this T&C stated that if the FTSE 100 index falls by 40% at the maturity date, you will lose 40% of your capital.

This sounds like the same pain that an ordinary share investor would face in similar circumstances, right?

Not quite – a shareholder would have received six whole years of dividends payments during the six-year term. This dividend cash (whether reinvested or not) would cushion this blow.

Over a six-year term, that dividend cushion would be huge. 4% received annually would roll up to 26.5% of the original investment.

This means that if the index has fallen by 40%, a shareholder would only be in the red by 26.5% – 40% = -13.5%.

You, as the structured product holder, would have lost -40%. Your loss is three times larger than a shareholder.

This is why some structured products are able to advertise rates of return that exceed the long-run average of the stock market. They actually exposing you to more risk than an ordinary index fund because the capital loss risks are larger than a shareholder would face.

You can learn more about how dividends help investor returns by reading some of the best dividend books.

Reason 6: Counterparty risk

When you invest directly in a wide range of companies, you spread the risk that any individual company might become bankrupt. This reduces your risk exposure without reducing return, which is why diversification is an excellent idea.

With structured products, you are completely dependent upon the solvency of the investment provider. You hold an ‘IOU’, not real assets.

FSCS protection doesn’t cover structured products in the event that a provider goes bust.

The companies that offer structured products are usually very large financial institutions with high credit ratings. However this won’t feel quite as comforting when I point out that failed bank Lehman Brothers was a major provider.

You cannot insure yourself against the failure of your investment provider. You can only protect yourself by investing no more than 5% of your wealth with one provider.

Reason 7: A fixed maturity date makes for an uncomfortable finale

On this blog, I promote holding shares for a long period of time, such as 5 – 10 years at a minimum.

This is because it is well documented that stock market indices can fluctuate very violently in the short term.

For pensioners approaching a retirement date, this poses a problem. If the cash is needed on a fixed date, then their time horizon shortens until they find themselves hoping desperately that the short term performance of the market will be kind, else they will be out-of-pocket.

To fix this, the best retirement planning books encourage savers to gradually move more of their funds into bonds as the retirement date approaches, so that by retirement date, their portfolio has become insensitive to swings in the market.

Structured product investors have no such coping strategy. They will find themselves riding the index rollercoaster and feeling stress and anxiety if the target is at risk.

In the high-risk product we discussed above, the difference between the FTSE 100 rising by 1% and falling by 1% could result in a 60% return versus a zero return.

Those are huge stakes, riding on a very unpredictable number. If that’s not a highly stressful investing experience, I don’t know what is.

And remember – these products are sold as being low to medium risk! Investors look too much at the risk of losing their original capital, and not at how the returns themselves could evaporate just a few days ahead of maturity.

Reason 8: Gambling blind

Do you know the probability that the FTSE 100 index will close above its starting level in three years time?

I certainly don’t! Only professional derivatives traders will have access to derivative pricing information which will allow them to derive that answer.

How can an investor make an informed investment if they are not told this number?

The silver lining of structured products

Most of the insights that I have shared, indicate that buying shares and investing in the stock market is more efficient and in some cases, lower risk, than structured products.

But I have identified some circumstances where a structured product might have a place in a portfolio.

Structured products tend to deliver a superior return when the market is going nowhere. Including a structured product in your portfolio could enhance returns in tepid market conditions.

This could come at the expense of capping your returns if the market rises strongly, but for many, this is a happy trade-off.

If used wisely, structured products could nudge your portfolio return towards the target 5-8% annual return range. They could reduce volatility.

However, such products should not be overused, as their linkage to the same indexes means that their performance will be strongly correlated (either they all succeed, or none succeed), which would work against the objective of smoothing your returns.

Conclusion

Structured products are opaque vehicles. There are many opportunities for investors to misunderstand the real risk and reward of these investments.

It is quite easy to fall into a trap of thinking that structured products have a magic formula that produces stellar returns without the risk of the stock market.

Now that you understand how structured products work, you’ll appreciate that this couldn’t be further from the truth.

However, once you understand the internal mechanics of these black boxes, you can step back and consider whether these derivatives (for a fee) could actually stabilise your portfolio if used in moderation.

I strongly recommend that you engage with a financial adviser before investing in a structured product. You should also use this checklist of what to look for when researching a structured product. Some providers actually give you no choice – they only accept referrals through financial advisers.

Course Progress

Learning Summary

How do Structured Products Work?

A structured product might look like a stock market investment, but it is an IOU with a single company.

Structured products pay a return based upon whether certain conditions are met, such as the performance of an index e.g. FTSE 100.

Structured products usually provide full or partial 'capital protection', which means that you may receive your stake back even if the index falls.

Behind the scenes, a structured product is a combination of low-risk bonds and financial instruments called 'derivatives'.

The bond is designed to protect the original capital, and the derivatives provide the bonus return in certain circumstances.

Derivatives are used in higher-risk products to add risk to the product (such as capital losses in the event of a sharp fall in an index). Striking this deal allows a provider to provide a higher bonus in return.

These products are designed to appeal to our risk averse brains. They minimise the probability of any loss. But this this is often a trade-off because the worst case scenario is sometimes more extreme than an one an ordinary shareholder would experience.

These principles guide the portfolios of sophisticated investors. Professionals spread their bets over many individual investments and also cover multiple asset classes with low correlation.

Quiz

Next Article in Course

Before you move on, please leave a comment below to share your thoughts. I respond to all comments.